Keith Haring always thought of himself as a funny-looking kid, which might be why kids all over the world responded to him. Keith said, ” I found out that I can make any kid smile. It’s probably from having a funny face to begin with – and looking and acting like a kid. And kids can relate to my drawings, because of the simple lines.”

“When you’re 8 or 9 or 10,” said Keith’s best childhood friend, Kermit Oswald, “you look across the classroom and there are people who stand out as real dorks and some who turn out to be kind of interesting. There was always something interesting about Keith. It was the way he dressed, it was the way he talked, it was the way he would smile, smirk, and roll his eyes. It was the way he could get himself out of trouble as fast as he could get into it. Anyway, Keith and I were always known as the artists in the school. We were both crazy about drawing.”

Keith Allen Haring was born on May 4th, 1958, in Reading, Pennsylvania. But the Harings lived in Kutztown, a nearby Pennsylvania Dutch farm community, where Keith was raised. In time, Keith became “big brother” to three sisters, Kay, Karen, and Kristen. The family lived a sheltered small-town life, with Keith’s father working as a supervisor in a communications firm located in Allentown, and with his mother raising the children.

“Before Keith was even a year old,” recalled Keith’s mother, Joan, “he used to sit on his dad’s lap after supper just drawing some gobbly-goo with crayons he’d been given. Then, later, his father, who was very good at drawing cartoon things, would show Keith how to draw circles. Then, he’d make a circle into a balloon or an ice-cream cone or make a face out of it, and put ears on it or make all kinds of animals. And that’s how it all started.”

From the first, Keith’s art teachers in Kutztown were astonished at the boy’s obsessive love of drawing. Said one, “With him it was an inborn thing.” Another said, “Keith loved line. Anything that lent itself to line pattern, he loved. He worked so intricately! The way the pattern would carry through and around and in and out was just extraordinary. He had such imagination!”

In high school, Keith knew he wanted to become an artist. Although he loved the cartoon characters of Walt Disney, Dr. Seuss, and Charles Schultz (especially Charlie Brown), he now wanted to do abstract drawings. He started making little shapes that together would fill whole areas, with one shape leading into another shape, and with a line that seemed to flow endlessly – that could go on and on.

During a church trip to Washington, D.C., Keith visited the Hirshhorn Museum and there he saw a group of Marilyn Monroes by pop artist Andy Warhol. He was struck by the strong flat images and looked at them for a long, long time. Throughout his whole high school period he looked at art and studied art, because he knew that art would be his life.

But on the way, Keith got into trouble.

“I was 15 when I began hanging out with a lot of kids who were troublemakers,” he said. “We were a whole bunch of friends doing this, we’d go to concerts like the Grateful Dead – and I was letting my hair grow longer and longer, because, see, I wanted to be a hippie. I started experimenting with all kinds of drugs – and it really messed me up. My studies at school got worse and worse – and I did really stupid things. My parents were in a state about me. But I just had to break out of the conformity of Kutztown – I felt I was suffocating.”

Keith’s mother said, “We tried to get him to change, to stay home more, to study more. At fifteen, sixteen, we thought he was wasting his abilities, not making the most of his school years, spending too much time messing around. We felt we were failing, and yet we didn’t know how to cope. We didn’t know how to change him.”

“I often felt I should have spent more time with Keith,” his father, Allen, admitted. “Often we did things as a complete family, but having three girls and one boy, we ended up satisfying the majority rule – things that the girls wanted to do, not necessarily what Keith and I wanted to do. But even earlier on I felt I wasn’t really getting through to him, because when we did do things together, we almost never talked. Then, when he was with his druggy friends, I just felt I wasn’t breaking the ice. Maybe I didn’t try hard enough. I couldn’t get us together.”

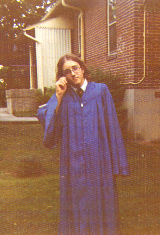

Soon, however, Keith began growing out of his recklessness. He came to realize that drugs and bad company were holding him back. By the time he graduated from high school, in 1976, nothing was going to keep Keith back, and he felt grown-up enough to leave home, leave Kutztown, and look ahead to a future in which art would be his focus.

“When Keith left home I remember standing at the kitchen door just weeping,” said Keith’s mother. “I was just so relieved that when he left he wasn’t the problem he had been earlier. I’ll confess it was almost a relief not to have the loud music going all the time. But I missed Keith terribly – just terribly.”

Part of Keith’s journey toward independence involved coming to terms with the fact that he was gay. Confusing as it had been some years earlier, he gradually became comfortable with this aspect of his life, and with this acceptance came a sense of liberation. “I was happy, because I suddenly found that my art was blossoming as was my sexuality, and opportunities seemed at hand,” Keith said. “I wasn’t sure of any of it, but believed in the fact that whatever was happening was happening for a reason. So I went along with the flow – and I let whatever happened happen.”

Keith attended art school in Pittsburgh – the Ivy School – but switched to another, The Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, where he was given his first solo art exhibition. In 1978, at the age of 20, Keith decided to go to New York City where he enrolled at the School of Visual Arts, and where he began to enter the chaotic yet exhilarating stream of the New York art world.

“The School of Visual Arts was great,” said Keith. “I took basic foundation classes, which meant classes in drawing, painting, sculpture, and art history. Later, I took course in video art, semiotics, and in performance art. Everything was very exciting – living in Greenwich Village, having my own apartment and going to school. And it was great meeting Kenny Scharf and Jean-Michel Basquiat, who became my friends and also wanted to become artists.”

All of Keith’s teachers at the School of Visual Arts remembered him as being an unusually energetic and dedicated student. Said Jeanne Siegel, the head of the Fine Arts Department, “Right from the beginning the thing that struck me about Keith was that here was a young man who was very directed and very determined. He knew what he wanted to do and then he did it. And he was producing eccentric works as compared to the other students.”

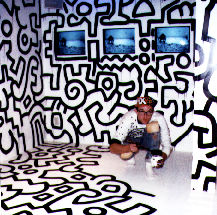

New York in the 1980s was a place where lots and lots of things were always happening. Kids from all over America were coming to the East Village to live and to create. They were a whole new generation taking over from the fast-fading hippie culture. Keith was part of this feverish activity as he immersed himself in the club scene, the punk-rock music scene and especially in the graffiti scene, which was blossoming on the streets and in the subway system of the city.

“Graffiti were the most beautiful things I ever saw,” said Keith. “The kids who were doing it were very young and from the streets, but they had this incredible mastery of drawing which totally blew me away. I mean, just the technique of drawing with spray paint is amazing, because it’s incredibly difficult to do. And the fluidity of line, and the scale, and always the hard-edged black line that tied the drawings together! It was the line I had been obsessed with since childhood!”

In 1980, soon after leaving the School of Visual Arts, Keith began drawing his own graffiti on the streets. Like other graffiti artists, he invented his own tag or signature. Keith’s tag was an animal, which, as he continued to draw it, started to look more and more like a dog. Then, he drew a little person crawling on all fours, and the more he drew it, the more it became The Baby. In this way, Keith began to build his own personal vocabulary, which would vary and increase with the years.

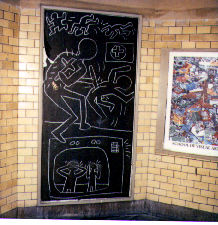

Because he had little money, Keith went everywhere by subway. One day, while waiting on a subway platform, he noticed some empty black paper panels which were used to cover up old advertisements against the platform walls. Keith thought, “These panels are just dying to be drawn on!” Then and there, he rushed out of the subway, bought some white chalk, came back and began drawing on the black panels.

The drawings were quite simple – pyramids, flying saucers, human figures, winged figures, television sets, animals, and babies. Soon the baby with rays all around it became a kind of signature, and the people of New York who rode the subways began recognizing these drawing, although they had no idea who made them.

“Every two weeks, I’d add new elements to the drawings,” said Keith. “Often I’d do thirty or forty drawings in one day. Now I found a way of participating with graffiti artists without really copying them, because I didn’t want to draw on the trains. Actually, my drawing on those black panels made me more vulnerable to being caught by the cops – so there was an element of danger. Well, I started spending more and more time in the subways. I actually developed a route where I would go from station to station to do just those drawings.”

For fun, Keith and his many friends spent their nights at the Paradise Garage or at Club 57, an East Village hangout, where Keith would do performance pieces involving the recitation of poetry, the showing of videotapes he made himself, and the acting-out of various crazed charades. Mostly, Club 57 was a place where everybody seemed to lose their inhibitions, dancing madly and generally having a pretty wild time.

During this time, Keith supported himself by working at various downtown clubs. At Danceteria he was a busboy. At the Mudd Club he organized underground art shows. At one point, he worked as an assistant to a gallery dealer named Tony Shafrazi.

Before too long, however, he began selling more and more of his own work out of his studio. Earlier he had resisted going with a gallery – “I just felt that the whole gallery situation was incredibly confining,” he said – but now the need for a gallery seemed essential. And so began Keith’s professional association with the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in SoHo.

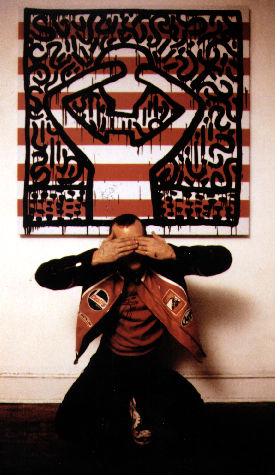

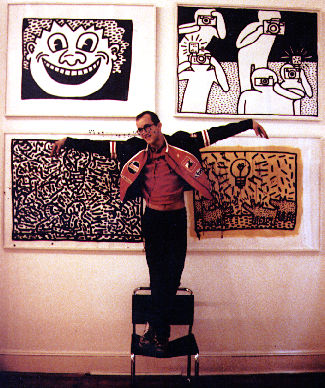

Keith’s first show there, held in October 1982, was a fantastic success. Carefully orchestrated by Keith and his dealer, the exhibition drew some 4,000 people and was designed to show Keith at his most prolific and electric. The works on view reflected every facet of his interests, from the street styles of breakdancing, rap music and graffiti to the sexual freedom of the period and the greater interchange between races. Critics called the exhibition dazzling in its inventiveness and energy – and the name Keith Haring was suddenly part of the city’s avant-garde.

Keith’s parents were proud of their son’s success. As his mother remembered, “We never knew what Keith was doing would ever be anything big. But after he had been in New York for two or three years, he came to visit. He reached in his pocket and pulled out ten $100 bills. I said, ‘What’s that?’ And he said, ‘I’ve sold some more things. And this is to pay you back for some of the money you’ve given to me over the years.’ I said, ‘My goodness!’ He said, ‘Things are good!’ Well, at that point we still didn’t know what he was doing. But it was clear that there was a lot going for him – the subways, the clubs. Then that show at Tony Shafrazi – we thought it was just great. And that’s when people started going up to him and saying, ‘Wow! You’re Keith Haring! Will you sign this?’”

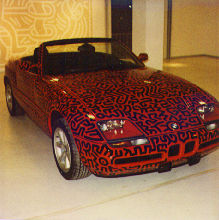

Almost immediately, Keith was invited to exhibit in Europe – in Holland, Italy, Belgium, and England as well as in Japan. Everywhere, people responded to a style that combined the simple with the complex, that blended color and pattern to form dynamic images of great variety and originality. And it was a style that mysteriously suggested the artistic traditions of Africa, Asia, Australia, Oceania, and the Americas. There were also powerful images of social consciousness, for Keith looked at the world, and at the struggles of the oppressed, and through his art made his feelings known. Over the course of his career he called attention to causes by creating works to promote literacy, support UNICEF, work against apartheid in South Africa, and fight drug use. Because Keith was gay, he made a special effort to spread awareness of AIDS, making works of art that warned young people against unsafe sex.

Gaining more and more attention and success, Keith began to expand his creative horizons by painting major on-site murals all over the world and designing large-scale outdoor sculptures that resembled huge, brightly colored children’s toys. Two great honors came to Keith when, at the age of 27, he was invited to show the entire range of his work – from 1980 to 1985 – at the Bordeaux Contemporary Art Museum in France and at the Stedelijk Museum in the Netherlands.

In whatever part of the world Keith found himself and no matter what honors came to him, he would always insist that children be a part of his appearances. He set up workshops with them and always made sure that everyone had a lot of fun.

“What I like about children is their imagination,” he said. “It’s a combination of honesty and freedom they seem to have in expressing whatever is on their minds. So, whenever I could, I did projects with kids.

“There’s one I did as often as possible: I rolled out this big roll of paper. All the children sat around it. I’d do some drawings with markers or pens. I’d have music going and, as in ‘musical chairs,’ when the music stopped everyone moved to another part of the paper. When the music started, everyone continued to draw. It was a way of filling the paper in an interesting way. I’ve done this project in Japan, all over Europe and America – and it worked every time. It never got boring.”

Nothing in Keith’s life was boring either. He loved to party and loved to surround himself with lots of talented and beautiful people, many of whom had a great appreciation for his work. One of these was Madonna, whom Keith met when they were both just starting out in the East Village.

“We were two odd birds in the same environment,” remembered Madonna. “I watched Keith come up from that street base, which is where I also came up from. I’ve always responded to Keith’s art. From the very beginning there was a lot of innocence and a joy that was coupled with a brutal awareness of the world. The fact is, there’s a lot of irony in Keith’s work, just as there’s a lot of irony in my work. And that’s what attracts me to his stuff. I mean, you have these bold colors and those childlike figures and a lot of babies, but if you really look at those works closely, they’re really very powerful and really scary.”

Another friend was the artist Roy Lichtenstein, who said about Keith’s work, “When Keith finishes a piece, there’s nothing you could think of that you’d want to change. Even if he did something all at once – without standing back and changing anything – there just isn’t a false move. It’s all beautifully drawn – and there’s such a sense of relatedness. The stuff is beautiful!”

Yoko Ono, the widow of John Lennon, said about Keith, “He always stood outside the art world, because his art is the people’s art. In that way, he is like a record producer of pop music – of groups whose songs reach out to the people. John Lennon did that, and the Beatles did that in the sixties. Keith is doing exactly the same thing, and that’s why he communicates on such a big level.”

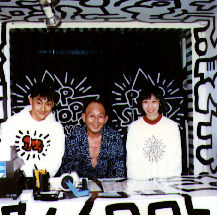

In 1986, Keith opened his Pop Shop on Lafayette Street in SoHo, where Keith Haring T-shirts, caps, buttons, prints, inflatable babies, and many other Haring-designed products would be sold. This was a very bold step, because it lay Keith open to charges of having sold out and becoming commercial. But following the advice and encouragement of his friend, Andy Warhol, Keith went through with the idea. He said, “I wanted to continue the same sort of communication as with the subway drawings. With the Pop Shop I wanted to attract the same wide range of people, and I wanted it to be a place where not only collectors could come, but also kids from all over and everywhere.

During the time that Keith had been rising in the art world, he had lost a number of close friends to the fatal disease of AIDS. Toward the end of 1988, he noticed a purple spot on his leg, a sign of an AIDS-related cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma. His doctors confirmed that he, too, had AIDS. At first, it did not affect his work habits or his hectic travel schedule. But as the disease progressed, he became weaker and weaker until he was barely able to hold a pen.

“At first you’re completely wrecked,” Keith said. “You go through a major, major upset. So the first thing you do is, you kind of break down. I went over to the East River on the Lower East Side and just cried and cried and cried. But then you have to get yourself together and you have to go on. You realize it’s not the end right then and there – that you have to continue and you’ve got to figure out how you’re going to deal with it and confront it and face it.”

“You can’t despair,” Keith continued, “because if you do, you just give up and you stop. To live with a fatal disease gives you a whole new perspective on life. Not that I needed any threat of death to appreciate life, because I’ve always appreciated life. I’ve always believed that you live life as fully and as completely as you can. Actually, I’ve always felt that if you have a long life, it’s a gift – and you’re lucky if that happens to you. But there’s no reason to count on it.

Keith Haring died of AIDS on February 16, 1990. He was 31 year old.

At a memorial service, his sister Kay gave a moving tribute to her brother. “I remember that Keith was always drawing,” she said. “It was his hobby, his pastime, his vehicle of expression, his very being. So, you see, it has always seemed to me that the brother I grew up with is the same brother that all of you know. Only the neighborhood get-togethers became the Manhattan club scene; the art projects with kids grew to include thousands and thousands of youths; his generous nature reached to touch virtually millions; and the canvas on which he drew became the whole world.”

Today, a vast national and international public remembers Keith Haring for his strong, provocative, often smile-inducing works. But it is the children of every nationality and all walks of life that will remember Keith as their very special friend.

One of these, a 11-year-old boy named Sean Kalish, remembers Keith this way: “I was a friend of Keith’s. I used to go to the Pop Shop all the time with my mom. One time, when I was five years old, this very nice man in the shop asked if my mom and I would like to meet Keith. He took us to Keith’s studio.

“Keith was very nice. I thought he drew his art especially for kids. I liked the baby the best. The dog was my dad’s favorite. In the studio, Keith said, ‘Let’s draw!’ and that was neat. Later, Keith and I worked together on some etchings. There were these big metal plates. I would be working on one, and he would be working on one. Then we would switch and keep on drawing. I like drawing, because it’s something you can do with someone else. I liked to draw with Keith, because he drew just like a kid. Now there won’t be any more Keith Haring drawings. I wanted him to keep drawing for his whole life!”